The previous year’s weather in September & October, 2010 had been very rainy. However, this year autumn was warm, and the weather forecast promised pure sunshine itself, nor a drop of rain, and even relatively high temperatures during the day (at night frosts were expected, but this was not a problem due to us having several warm sleeping bags). The plan was as follows: First, spend a few days in a tent in Bon Echo Park, then go to Algonquin Park, where we had reservations (along with other group members) at a radio observatory facility, and finally, depending on the weather, a plan to canoe to Bates Island on Lake Opeongo in Algonquin Park, the site of a black bear attack 20 years ago and spend one night on that very campsite… if we dared!

The park has over 600 camping sites (often all of them are occupied), the majority located near Lake Mazinaw, but in my opinion the best campsites are in the middle of the park (5-6 km from the main gate), at Hardwood Hill. Most of them are completely sheltered and private, you cannot hear the road traffic as well as that area is much quieter because usually families with young children prefer to camp closer to the lake, where the campsites are much more ‘open’, yet closer to the museum, showers, canoe rental place and the amphitheatre. Unfortunately, the campsites at Hardwood Hill closed on the Monday after the September Labour Day weekend, so we had to settle for the campground closer to the lake (the park remains open until the Thanksgiving Weekend in October). Although they did not offer too much privacy, it was not a problem because the park was almost empty. After perusing the area, we chose site no. 16. It was located at the bottom of a rocky hill and we were surrounded by trees with falling leaves of different colors which created a beautiful, picturesque leafy carpet! Despite the fact that our site was generally open and bordered with other campsites, it was not a problem as no one else arrived to camp around us, except for a giant school bus whose driver was totally lost en route picking up school aged campers.

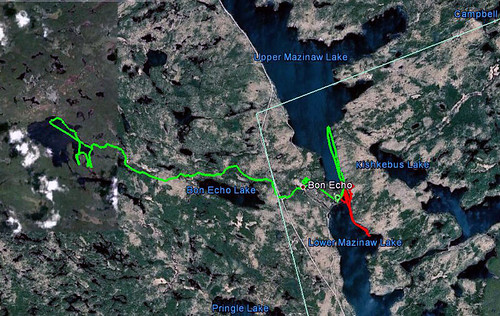

This time we did not bring our canoe and decided to rent one, hoping for cheap rates. Indeed, the canoe rental place, operated in the park for over 20 years by the same gentleman was open and offered a great deal—for just $ 30.00 we could use a canoe for 4 days on Lake Mazinaw (where the canoe rental hut was located) and on Joeperry Lake, located in the middle of the park, where several canoes were already waiting for us! I had never canoed on Joeperry Lake due to a one-kilometre portage from the parking lot.

We paddled twice on Lake Mazinaw, canoeing along the Bon Echo Rock, admiring Indian pictographs, impressive rock formations, cedars growing on almost bare rocks (some more than 1000 years old, thus forming one of the oldest forests in North America) and the inscription on the rock, containing a few verses from the poetry of Walt Whitman. We were lucky to paddle near the Rock at the sunset, when the setting sun’s rays illuminated the rock; this is certainly a very exceptional phenomenon, when the whole rock becomes bathed in sun and turns orange. In the summer a lot of tourists show up at the beach, watching this amazing show. At the beginning of the twentieth century Flora MacDonald, the proprietress of this place, published a publication called “Sunset of Bon Echo”—although the term “Sunset” was derived from the name of a local Indian Chief, it was the most appropriate name indeed! The day when we were canoeing, when the rock was almost shimmering with astonishing orange colours, it was also very windy and the lake was quite rough; even though Catherine bravely paddled, I could hardly take photos, as I had to grab the paddle and position canoe so that the waves would not tip it over.

We also managed to climb to the top of that massive rock. There are two ways of ascending it—one is climbing on the sheer wall of the rock, reserved only for the courageous members of the mountaineering club; the other—which we had chosen—is a walking trail, used by the remaining 99.99% of tourists. The trail is not difficult, in some places metal stairs were installed (as well as the remains of the old stairs can be seen, which were used in the early twentieth century). It took us less than one hour to reach the summit of the rock. From there, a beautiful view of Upper and Lower Lake Mazinaw unfolded—two parts of the lake separated by the so-called ‘Narrows’, a strait. There are unconfirmed legends about the battle fought by Indian tribes at the top of this rock, where defeated warriors threw themselves (or were pushed) into the depths of Lake Mazinaw… It is also believed that the tribe who controlled the top of the rock wielded power over the canoe routes in the area. Somewhere at the top of the rock supposedly was a bunch of stones, arranged in a specific way by Indians, but I could never find them. In any case, this impressive rock was certainly a very special, sacred place for the Native People and the existing hundreds of pictographs attest to the exceptionality of this place.

At the beginning of the twentieth century a hotel was built there and prospered for many years (Bon Echo Inn, burned down in the thirties of the twentieth century); a bridge was also built over the Narrows, allowing tourists to get to the other side and climb to the top of rock. Currently, a small boat frequently operates from the park, carrying tourists to the opposite shore. A lot of well-known photographers and painters visited Bon Echo and produced beautiful images of the rock (among them were members of the famous Canadian “Group of Seven” and Malak, the photographer whose photo of the tulips in front of the Parliament Building in Ottawa for many years had graced one side of the one dollar bill—and on the other side of the bill was the photograph of Queen Elizabeth II, taken by his brother Karsh). In 2007, during one of my meetings at my naturalist club, I talked with an older gentleman, who recalled how in the 1960s he and his wife chose to swim naked in the evening in the lake near the ‘Narrows’ at Bon Echo! He also mentioned a writer whom he met and who was at that time living at the park; of course, it was Merrill Denison, who had the right to live in his home until his death (currently his home is a museum and gift shop). When I went to the club’s first meeting in the fall of 2011, it turned out that he had recently passes away. I will always remember his stories about Bon Echo Park!

Of course, we also went paddling on Joeperry Lake. Indeed, the lake was located quite far from the parking lot and neither I nor Catherine would have been willing to carry even a light canoe to the lake (and back), so we were very happy to use one of the rental canoes, already placed on the shore of the lake. Joperry Lake turned out to be very picturesque and we were surrounded by brilliant autumn colors. A number of interior campsites dotted its shores, yet only one was apparently occupied. We wanted to paddle around a big island, but the narrow passage was too shallow even for a canoe, so we simply paddled all over the lake, admiring the spectacular autumn colours and came ashore at sunset, as it had already darkened. Using flashlights, we walked to the car and in complete darkness we drove the 8 km. to our campsite.

At one point I stopped and showed Catherine a very interesting rock near the road: probably due to the weather conditions, it had broken in two and in the middle of this chasm grew a beautiful tree! I had spotted the rock for the first time in the early 1990s and have been observing it since!

Every night a bunch of racoons visited our campsite and even our cooler, wedged under the picnic table, was a fair game for them and they tried to open it. Besides, they always barked loudly and fought among themselves, waking us in the middle of the night. Catherine did not sleep as soundly as me and several times flew out of the tent at night to shoo them away; it was practically a nightly ritual.

On October 7, 2011, after paddling for a few hours on Lake Mazinaw for a few hours, we left the park and took road number 41 north up to Algonquin Park, to the Radio Observatory. On our way we stopped in the town of Pembroke where I decided to try MacDonald’s coffee; unfortunately, it was so bad that I returned it and later drove to Tim Horton’s, for a cup of delicious coffee!

We arrived at our destination at dusk. Somehow Catherine had thought the trip commenced on the Friday evening, as was the usual OCEY (The Outing Club of East York) club scenario. However, we were told that we were a day early! We considered putting up our tent nearby, but Caroline, a most gracious host, happily put us up for the night in a small room which reminded Catherine of her 1960s teenaged flower power bedroom (hot green with modern furniture). Unfortunately, the 140.00/night room rate did not reflect the 1960's economy! By the way, the building we stayed in formerly served as a hotel and canteen for scientists who worked there.

The site consisted of the huge radio telescope, built in the 1960s, can be used for observation of distant astronomical objects using radio waves plus a 1960’s style house with 10 plus guest rooms, unisex bathrooms, dining area and lounge. The radio telescope was built in the sixties and has 46-year-meter parabolic antenna. For some time it was not used and even there were rumours of its demolition, but it eventually it was taken over by a private company, Thoth Technology, Inc., which hopes to restore it back to its ‘former glory’ (http://thothx.com/home) and incidentally to earn a little bit on this project. The CEO and the director are a married couple, Canadian and British; they both met while studying at Oxford. He has a PhD in astrophysics and is a professor at York University; his wife holds a doctorate in English and also teaches at York University.

The most interesting point on the agenda was a visit to the observatory; our guide was, of course, Ben. After driving for a few minutes, we arrived and saw the huge dish, it looked really impressive! First, we went to the ‘control center’ from which the canopy of the telescope can be operated. The control panel, as well as most of the instruments came from the sixties and looked at least slightly outdated in 2011! From the building we went down to an underground tunnel leading to the base of the telescope. Everywhere there was a lot of the old measurement equipment from the fifties and sixties; at that time all the equipment was considered to be extremely advanced; today it was more fitting to belong to a museum. For me, it was for me a great place to take pictures! The Observatory also had a huge atomic clock, locked in a special room with controlled temperature and additional power supply in the form of batteries, in case of power supply interruption. Then we visited the rooms located around the base of the telescope and then climbed on the terrace around the telescope, from where a marvellous view of Algonquin Park unfolded! We learned many interesting things about this telescope and I hope that this undertaking will be successful.

We took advantage of the available canoes and on Saturday we paddled on Lake Travers, reaching a number of campsites. Some of them had beautiful sandy beaches; considering that the temperature during the day reached +25 C (in October!), we almost thought we were in Cuba. After paddling for a while, we reached the end of the lake, where it narrowed and turned into a river (Petawawa River). The next day, on Sunday, we decided to paddle up that river as far as possible. Incidentally, the Petawawa River, after leaving Algonquin Park, runs through the town of Petawawa and the Petawawa military base. From this base a lot of Canadian soldiers depart on their missions to Afghanistan; sadly, some never return… Eventually we reached rocky rapids and it was not possible to proceed any farther without portaging the canoe.

Nearby we saw the remains of ‘log chutes’, special shafts used to transport logs over water in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. This year Thanksgiving Day in Canada fell on Monday, October 11, yet a traditional turkey dinner was to be held on Sunday since everyone was leaving on Monday morning. It was quite late and we were still about 10 km. from our ‘hotel’ and did not want to be late for this traditional meal.

After breakfast on Monday morning we said goodbye to our hosts and the other participants and set out on the third leg of our journey, to Lake Opeongo, located also in Algonquin Park, but in its southern part, near highway 60 (in a straight line it was just 40 kilometres from us, but the park does not have many roads and thus we had to take a very circular route). We stopped briefly at Barron’s Canyon where Catherine walked to the spectacular cliffs as well as visited the Archway Campground. The park’s interior campsites are open for the whole year, but on this very day all drive-in campgrounds, except for Mew Lake, were closing, so there was plenty of activity at Archway, with families packing and leaving the park. Once the Canadian National Railway, built in 1915 and dismantled in 1995, crisscrossed Algonquin Park and ran through the Archway Campground; now its rail bed is used as a hiking and cycling path. We also visited a small, old wooden house which once housed park wardens who worked in the park. One of the wardens who occupied this building was Tom Thomson, the famous Canadian painter, whose paintings nowadays sell at auctions for record-breaking prices. Tom Thomson is always associated with the famous Canadian group of painters, “Group of Seven”, as well as with Algonquin Park, where he worked, canoed, painted his famed paintings and where he mysteriously drowned in Canoe Lake. Although my GPS supposedly calculated the fastest route, some of the roads it selected were quite rough; one of them initially seemed to be quite nice and picturesque, but after driving for several kilometres, it became too rugged for my car and we had to turn back, deciding to stick to main roads instead. Eventually we reached highway 60, drove through Wilno and Barry’s Bay and after a few hours we arrived at Lake Opeongo…

Our intention was to rent a canoe and paddle to Bates Island on Lake Opeongo and spend one night at a very specific site. Well, exactly to the day, 20 years ago (11 October 1991), a couple camped on Bates Island on that campsite and probably on that very first day they were attacked by a black bear. They both died and only after 5 days did anyone realize what had happened. When the park staff arrived at the island, the bear still was at their campsite, guarding their bodies... It was the last fatal black bear attack in the park since then.

As it turned out, canoe rental was more expensive than we expected; even though we were going to rent a canoe for less than 24 hours, we were required to pay for two full days. It was also widely advertised that a rental was only $14.95 if you were staying in the park campground, but it turned out that interior camping did not count as a park site so the price immediately started at the regular rate of $20.99 for an aluminum canoe. All told we calculated our 18 hour rental would have been close to $60.00—what a rip off! It was not really about money, we simply felt this deal was not fair, especially considering it was the last day of the seasons and the prices should reflect that. After talking with the manager, who insisted that we pay the full price and did not want to give us any discount, we decided to opt out of paddling to the interior site on Bates Island and instead camp at some drive-in campsite in the park.

It is interesting, but over the past 15 or so years I have encountered many similar situations in Ontario. For example, 13 years ago, in late September/early October, we wanted to rent a cottage (and due to the bad weather, at least 90% of all the cottages were vacant). The owner graciously said that she would give us a 10% discount... off the full price of $800 per week... Another owner got visibly upset and unpleasant when we presented her a flier (which she must have created, approved and distributed), advertising a special fall rate of ‘$350 per cottage per week for 2 people’ (by the way, during our stay all the other cottages remained vacant). Or when 12 years ago we wanted to rent a fishing boat, again at the end of September, the price was firm $100 plus gas—and we also had to be back by 5 pm. Or when we tried to rent a cottage relatively close to Toronto, again in early October—even though we had all the linens, the owner quoted a ridiculously high price, which I would have probably been reluctant to pay in the peak season; when I asked him for a discount, he said, „I don’t make money by giving discounts”. Well, he certainly did not make ANY money then! I could certainly throw in many other similar examples. On the other hand, while travelling in the USA, I was so surprised at how it was possible to negotiate prices of motels or rentals. Apparently, the attitude towards business in the USA is... well, more business-like and customer-oriented! Considering that in Ontario most of the tourists are gone after the long Labour Day weekend in September, it would be only natural to see substantial discounts offered then.

We went to the park office adjacent to the store to inquire about campsite availability, yet the park employee gave us completely wrong information: she said that several other campgrounds were still open and (supposedly!) called one of them, confirming it was open. When we arrived there, it was closed and after unnecessarily driving to and fro, we eventually discovered that all campgrounds but Mew Lake were closed for the season. So, we finally reached Mew Lake, which is open all year (some people live there in RVs throughout the winter and Catherine spent the previous winter weekend in one of the yurts). We got campsite no. 68; its location was below-average: it was very close the campground’s roads, we could also see (and hear) the traffic on highway 60, it was exposed and there were a few other campers around us. But we did not care that much, we were supposed to spend only one night there and it was to be the last camping night of the season. We pitched the tent under an interesting tree with plenty of branches, started a campfire and sat around it for a long time as it was quite warm at night, about +14C. In general we were extremely lucky with the weather: for 8 days, every day was sunny, there was not one drop of rain and daily temperatures were reaching +25C (after arriving in Toronto the next the day, it began to pour!). Before midnight we went to the tent and turned in. Practically, we had no food left and we did not even bother putting away our stuff into the car; we even forgot that there was a coffee cream in the cooler (which Catherine bought today for the morning coffee).

”Jack, there is a bear at our campsite!”

At 2:15 in the morning I woke up and heard Catherine getting out of the tent, as well I pick up some noises coming from outside—same noises as we heard nightly in Bon Echo.

Raccoons again, I thought, half-consciously turning on the other side and heard Catherine chasing them away and shouting, “shoo, shoo”. But in a few seconds she came back to the tent.

“Jack, there is a bear at our campsite”, she said calmly.

Immediately I woke, grabbed my glasses and reached for the flashlight.

“A bear? Are you sure”, I asked. “Maybe it’s just a big raccoon?”

Some raccoons are so adept in stealing food from tourists at campsites that they become obese and look like little bears, especially in the dark. In the 1990s a park warden in Bon Echo park told me that many times he had been contacted by frighten tourists who reported seeing a bear at their campsite; once he arrived to investigate, it turned out that this ‘bear’ was just an overfed, fat raccoon.

“No, it’s a bear”, she said.

I scrambled out of the tent, without even putting on the shoes. It was full moon; my car and the park bench were fairly well lit—they were about 8 meters from us. From the other side of the car, where I could see the white bottom of the cooler, came a crackling sound, but I did not see its source, everything was drowning in darkness, hidden in the shadow of the car.

I decided to see the perpetrator of this noise and quietly walked to the cooler. Indeed, I saw a black object near the cooler which looked like a bear, but it did not appear too big or scary. I quickly walked back to Catherine.

“Maybe it’s a small bear”?

“No, it’s not a small bear, it’s a big bear”, she firmly said.

Big one. Admittedly it was a clear sky, full moon and Catherine is not given to wild imagination or hysterics unless it involves crawling bugs in the bed.

We did not know what to do. The bear ostensibly relished the coffee cream, as it was the only thing in the cooler. I had a bear banger with me, but did not feel that I had to use it. However, the bear spray, which would be the most appropriate device to drive away the bear in case of further problems and which I ALWAYS kept in the tent, this time—and probably for the first time—was locked somewhere in the car, because we had not even thought about the possibility of having to use it here! So, while we stood helplessly around the tent, staring at the bear, he leisurely drank the coffee cream. We were patiently waiting until he would finish it.

Indeed, after a few minutes we heard a different kind of noise… and suddenly a huge, black hulk appeared from behind the car. Undoubtedly, a black bear! He went over to the park bench where more of our equipment was all over the table and standing up on his hind legs, he started to nose through our stuff. We could see him perfectly now. It was definitely a BIG bear. He certainly was aware of our presence—after all, when Catherine initially approached it, thinking it was a bunch of raccoons, she was no more than 2 meters from it and he must have seen and heard her—but he was totally not interested in us. His front paws rested on the table and he was checking the content of our plastic box, where we usually kept our kitchen equipment and other similar implements. Although we did not keep any food in the box, for some reasons a bag of dried prunes was there, which of course he found. Nevertheless I have to admit that the bear was a gentleman—after all, he could have dumped the whole box on the ground and gone over everything then, picking what he needed, but he did not do so, instead sniffing all over the box on the table. It lasted for maybe two minutes.

“Perhaps we should climb the tree?”, Catherine suggested, “and observe the bear from there?”

She had never been close to a bear before except at a dumpsite and relished the idea of spying on him from 10 feet away

The tree under which we set up our tent had ideal branches for climbing and we could have done it very easily. I’m glad we did not, though; I have read that the bear, seeing something moving up the tree, might become curious and climb the tree himself to further investigate. I began to regret that I did not have my camera handy, yet I do not think it would be possible to take photos without flash. Once the bear found the bag of prunes, it grabbed it with his teeth and walked to the same place as before, i.e., the other side of my car. Soon we heard the rustling noise of the aluminium bag and loud munching.

Interestingly, I was not afraid, even though the whole spectacle was a bit surreal. Generally, black bear attacks on humans are extremely rare and if they do take place, then the culprit usually is so-called ‘predatory bear’, mostly a solitary male, who had been watching and following his intended victim for some time and then silently approaches and attacks the hapless individual when he least expects it. This bear, on the other hand, was a typical ‘campsite bear’, accustomed to people, cars, campfires, tents, coolers—he simply was searching for food, left by irresponsible tourists who did not hide it in the car or who did not hang it on the tree… The campers themselves, in the culinary sense, were not of any interest to the bear.

“What happens when he finishes eating the prunes”, I loudly asked myself. “Are there any other food items in the box?”

We were not sure; sometimes a bag of powdered soup could have gotten mixed up with the other stuff and we did not remember about it, as we totally forgot about the bag of prunes.

“You know, we should go to the car”, I said.

Quickly I ran to the tent, grabbed the car keys and slowly we headed towards the car’s front passenger door (just near the driver’s door, on the other side of the car, the bear was having his snack) and quietly got inside the car.

From the side window I had a perfect view of the big bear. He was sitting maybe a meter from the car, almost touching it. He was utterly disinterested in our presence (he must have heard the slamming of the car’s door) and kept devouring the prunes. We decided to stay in the car and simply wait for his next move.

After a few minutes he finished the bag of prunes and headed back toward the bench, climbed onto the table and sniffed the box. This time we saw him very clearly in the moonlight. He was pitch-black and once again we could admire his grandeur. Apparently he did not find anything else that was edible; as though not knowing what to do next, he looked left, right, at the car… and slowly headed in the direction of our tent, whose door was unzipped and wide open. Of course, we did not keep any food inside the tent—but after all, the bear could not know that! Who knows, maybe he would want to make a tent ‘inspection’, after which, besides holes in the mattresses, the tent would gain several extra doors, windows and even a permanent sunroof?

“Hey, buddy, the last thing we need it to have our new tent destroyed”, I said, started the car and slowly drove back.

The bear immediately vanished in the darkness; we did not even see which direction it ran. I switched off the car’s engine, opened the windows and we were listening for any clatter, but there was complete silence. In a tent at the adjacent campsite a few people were sleeping, not realizing what had just taken place just a few meters from them.

We stayed in the car for a few additional minutes and then went to the tent. The bear made a small hole in my cooler with his teeth—well, a great memento of this event—and a warning for the future! In spite of this highly unusual and remarkable experience, we quickly fell asleep and nothing bothered us anymore this night.

The next day morning Catherine went (alone!) for a walk along a hiking trail, located in the old railway bed (‘right of way’) of the JR. Booth Rail, relatively close to our campsite. Along the way she saw several bear poop. She met a couple who had camped at the Mew Lake Campground for decades and told them about the bear encounter. They were extremely surprised, as they had never seen a bear at this campsite! We were really lucky!

From my modest experience I can say that in the vast majority of cases, bears avoid contact with humans. Very often I see their fresh poop, but I hardly ever see bears—yet I am sure that they do see and observe us! For example, two years ago we were camping in the Massasauga Park and when we were away from our campsite for several hours, it turned out that a small black bear was wandering all over our site (a warden, who was in his boat nearby, saw it). Since all of our food was hung on a tree, the bear did not do any damage, did not take anything and had we not had the conversation with the warden, we would have never suspected that we had this furry visitor! While camping on Philip Edward Island, one night I heard crackling noises, as if somebody were breaking tree branches. I was sure it was a bear; when in the morning we left the campsite, we saw a bear standing on the shore. Bears do not seek any contact with people and when they sense their presence, they hide and at the most, watch them from afar, themselves remaining invisible and might visit their campsites in search of food at night or when campers are gone. At garbage dumps in Ontario one can sometimes see over 20 bears, rummaging everywhere and they totally ignore people coming there, engrossed in their food-finding mission. However, there have been cases when hikers startled bears or, even worse, mother bear with cubs (that is why it is suggested that lone hikers should loudly talk, sing or wear special bear bells) During such unexpected encounters bears might start puffing, snorting or stand on their hind legs and even make bluff attacks. In fact, such behaviour means that the bear does not want to harm us, but just wants us to go away—if they really wanted to attack us, they would have done it immediately.

Considering our aborted plans to canoe to and camp on Bates Island, the 20th anniversary of the tragic bear attack on the island and the fact that it was our last camping of the year, it was a very exciting conclusion of our camping and canoeing season! We were also taught a very good lesson to keep our food either in the car or hang it on the tree and keep all our foodstuff in one place.

Blog in Polish/Blog po polsku: http://ontario-nature-polish.blogspot.com/2011/10/w-parkach-bon-echo-i-algonquin-ontario.html